Which Artists Second Most Famous Work of Art Was Created Not Standing Up or Sitting Down?

When it comes to the High Renaissance, Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475-1564) is equally high as information technology gets. A peerless sculptor, good draftsman, and reluctant only skilled painter, he was not just ane of the best-known artists of his day but probably remains one of the best-known artists ever.

He could be a chip of a hot head: His rivalries with Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael are well documented, and he stormed out of the Sistine Chapel in a huff more one time. Merely he was so expert not even this reputation could drag him down. His contemporaries called him Il Divino ("the divine 1") because they accounted his masterful workmanship unparalleled amidst mere mortals. This nickname inspired the championship of the Met's sprawling exhibition devoted to the creative person, "Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer," opening Nov 13.

To pay tribute, we surveyed ten of his most pop works (based on Google Image searches). Here, we rank them according to where we retrieve they stand, critically, as representations of what makes Michelangelo awesome.

Michelangelo, San Spirito Crucifix (1492). Collection of the Santa Maria del Santo Spirito di Firenze, Florence.

10. San Spirito Crucifix (1492)

Michelangelo fabricated this nude crucifix when he was merely 18 years old. Information technology was a give thanks you to the Augustine monks at San Spirito who permit the teen couch surf afterward his patron, Lorenzo de Medici, died in 1492, leaving the creative person homeless. Past Giorgio Vasari'south account of the artist's life in his famed tome, theLives of the Artists, information technology was at San Spirito that Michelangelo began to dissect dead bodies "in order to study the details of beefcake, and began to perfect the swell skill in design that he subsequently possessed."

Despite existence and so drawn from life (or decease, every bit it were), the well-crafted crucifix didn't give Michelangelo's career much of a heave—in fact, almost forgot that he fifty-fifty fabricated information technology. Afterward centuries of being assumed lost, in 1962 a media tempest sprung upwards around it after the crucifix was rediscovered in a convent, covered over with hundreds of years of bad paint jobs. Earlier this twelvemonth, it fabricated headlines once again when it was finally returned to its original domicile in Florence, which probably accounts for its notoriety with the public.

The crucifix is juvenilia, still, which is why it ranks last on our list. The Christ effigy doesn't have the musculature for which Michelangelo was famous. In fact, it seems as if here he may have merely been copying previous artists' depictions. Art historian Margrit Lisner attributes the slenderness of Jesus's course to the patrons' wishes, merely also to an artist who was still green, prompting him to seek inspiration from earlier examples by other artists.

Michelangelo, Madonna of Bruges (1501–04). Collection of the Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk, Bruges. Photo by Elke Wetzig, Artistic Commons Attribution-Share Akin 3.0 Unported license, GNU Complimentary Documentation License.

9. Madonna of Bruges (1504)

Art historian Erwin Panofsky, when writing nigh Michelangelo'southward Madonna of Bruges, credited the creative person with saying that a perfect sculpture is i that can be rolled downhill without suffering damage. By those standards, this sculpture would come up shut to perfect: The sturdy, seated composition of Mary and the Christ Child recalls the size and compact mass of the original stone cake from which the figures were carved.

This was the look Michelangelo was going for and, at the time, information technology was quite innovative. Few sculptors had attempted a project of such complication at this scale, with the image hewn from a single slab of marble and continuing at 6-and-a-one-half feet tall.

Despite the mastery demonstrated in the Madonna of Bruges—and its status every bit the artist's only work to leave Italy within his lifetime—the sculpture owes its icon status mainly to the fact that it was looted by Nazis in 1945. Indeed, art historian William E. Wallace points out that the work was paid such scant attention that non even contemporaneous Michelangelo government knew much about it: "It was and then little known that his biographers Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi mistakenly believed it was cast bronze. Both the Risen Christ and the Bruges Madonna contributed piddling to Michelangelo'south Florentine reputation."

Clearly this was not the creative person's most memorable work—and so or now—and for that reason, we're ranking information technology number nine, power to coil downhill or not.

Michelangelo, Bacchus (1497). Collection of the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

viii. Bacchus (1497)

Deputed past Cardinal Riario, Bacchus was Michelangelo's first foray into large-calibration sculpture and is ane of the few works he would ever do that was not on a Christian theme. By tilting the effigy always and so slightly off balance, subverting the inherent expect of stability of the Classical contrapposto stance, the artist makes Bacchus—the Roman god of wine—appear appropriately tipsy. This level of realism was unprecedented in depictions of party-loving Bacchus up until this time, revealing Michelangelo every bit the virtuosic perfectionist he would go known as.

Reports point that Key Riario may have rejected the finished sculpture, suggesting that he didn't think Michelangelo's work was quite up to snuff nevertheless. Historian Ralph Lieberman explains that the Primal's distaste was shared past others, and he'd probably agree with our positioning it low in our ranking: "Riario'south reasons for declining the Bacchus could well have been the same every bit those for which many later commentators on the figure have disliked information technology: the awkward pose, the somewhat vulgar face, and the softly effeminate body."

Michelangelo, Dying Slave (ca. 1513–16). Collection of the Louvre, Paris.

seven. Dying Slave (1513–16)

Dying Slave was intended to accompany another piece of work, Rebellious Slave, on either side of Moses, in Pope Julius 2's tomb. In an attempt to select the perfect marble for the pope's final resting place, Michelangelo went to the quarries of Carrara to paw-select the slabs of rock. When he returned, he set to work chiseling a perfect specimen of man in the languid throes of death. And then Julius changed his mind and cancelled the commission.

Indeed, Dying Slave is one of six slave figures Michelangelo created over several years for the pope; Julius effectively drained the papal coffers dry out in an endeavour to create the perfect infinite for him to brainstorm his afterlife. But the project was never fully realized, much to the artist'south chagrin—specially subsequently having wasted nearly a year hanging around a quarry for it.

Could Dying Slave have been a better example of Michelangelo's penchant for perfection if he hadn't been thwarted by Julius'south ongoing fickleness? Difficult to say. As Richard Fly notes, the slave effigy itself seems frustrated by its own circumstances, as if to propose the figure's struggle with decease as a metaphor for the creative person's struggle with material:

Fifty-fifty Michelangelo, still, cannot sustain godlike supremacy over his material, and in several provocative works he appears to acknowledge that the invisibility of inert thing can almost neutralize even his creative powers. His statue of the Dying Slave… suggests that moment when life capitulated before the relentless force of dead matter… There is mayhap even a suggestion of something demonic and negating in the medium's ability to distort, frustrate, and debilitate the creative person'southward effort at creation: a suggestion of encroaching chaos.

Michelangelo, Angel (1494–95). The Angel of Arca di San Domenico in Basilica of San Domenico in Bologna. Photo by James Steakley (2008), Artistic Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

half dozen. Angel (1495)

This kneeling angel holding a candlestick, measuring merely about a foot and a half in height, is 1 of Michelangelo'due south earliest works. It was created for the Arca di San Domenico in Bologna as a companion piece to the artist Niccolo dell' Arca's preexisting angel, integrated inside the building's design scheme. It's historically important since it was with this work that Michelangelo started to showroom his signature style: while dell' Arca's affections is soft and effeminate, demure in its loving comprehend of its candlestick, Michelangelo'southward depicts a strong youth with defined musculature and hawkeye-like wings.

Despite its pocket-sized calibration, Angel reveals the artist's early command of his medium, and, as the appearance of any good angel should be, an omen of blessings to come. Fine art historian Ellen Longsworth argues that it functions a bit as an amuse-bouche for the artist'south more than famous work:

Fifty-fifty at a altitude the expressive integrity of Michelangelo'southward little saint is apparent. The primary contours communicate free energy and resolve, while the silhouette is perfectly legible against the backdrop of the ornate shrine. Not until Michelangelo'southward commission for the David would he face a like challenge. In outline a simpler figure than St. Proculus, the David was designed to exist read against the sky and the upper reaches of ane of the tribunes of the Florentine Duomo. The effigy's bodacious posture and alert turn-of-the-head, both immediately comprehensible from a distance, are too present in Michelangelo's fiddling saint.

Michelangelo, Moses (ca. 1513–15), for the Tomb of Julius 2. Drove of San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome.

5. Moses (1513-15)

Michelangelo's Moses came on the heels of his David, the public success of which had put him on Pope Julius's radar. Commissioned in 1505 past the pope for his tomb, the work represents a specific moment from the biblical tale of Moses, when he sees his people take started worshiping a infidel icon—the Gold Calf—merely later on he had trekked all the way downwardly Mountain Sinai with heavy stone slabs bearing the Ten Commandments. Needless to say, Moses was pissed, and it's precisely this anger that Michelangelo skillfully embodies in his eight-human foot seated sculpture. Moses isn't just sitting down, though. His left leg and hips shift left while his muscular body faces the right, imbuing the effigy with tension and power; although he looks left, his beard whips right, indicating swift movement.

Moses marks the middle of this list because the depiction of this biblical effigy is so expert. It may fifty-fifty be too good, co-ordinate to Freud, who quipped that this rendition was "superior to the historical or traditional Moses," adding that he thought that the sculpture had more secular than holy meaning, as a symbol of a homo repressing "inward passion" in the pursuit of a higher cause.

Michelangelo, Pieta (1498–99). Collection of the Vatican Museums, St. Peter's Basilica.

iv. Pietà (1498-99)

During the 15th century, the theme of Mary cradling Jesus one time he was taken downwards from the cross—other wise known as a pietà—was ordinarily depicted in Northern European art but less then in Italy. So when a French central approached 23-year-old Michelangelo to sculpt i for his funeral monument, the creative person gladly accepted the challenge, knowing he could make his mark. Information technology's the Pietà that made people make note of Michelangelo's name—quite literally, as Vasari describes:

…in truth, it is absolutely astonishing that the hand of an artist could have properly executed something so sublime and admirable in a brief time, and clearly it is a miracle that a stone, formless in the beginning, could ever have been brought to the state of perfection which Nature habitually struggles to create in the flesh. Michelangelo placed so much dearest and labour in this work that on it (something he did in no other work) he left his name written beyond a sash which girds Our Lady's breast.

Michelangelo, The Last Judgment (1536–41). Collection of the Vatican Museums, Sistine Chapel.

iii. The Last Judgment (1536–41)

"The twist into depth, the struggle to escape from the here and now of the picture airplane, which had always distinguished Michelangelo from the Greeks, became the dominating rhythm of his after works," Kenneth Clark one time wrote. "That colossal nightmare, the Concluding Judgment, is made upwardly of such struggles. Information technology is the most overpowering accumulation in all art of bodies in violent move."

Even that may be an understatement. The Final Judgment, which arcs to a higher place the Sistine Chapel's chantry, dramatically depicts the second coming of Christ and the concluding judgment of all humanity. Michelangelo squished 300 muscular figures into the sprawling scene, some representing prominent saints, others were mere mortals ascending to heaven or descending to hell. A scene of intense action, fear, awe, and copious nudity, the Last Judgment has been subject to much judgment itself, often criticized for its busyness and sometimes covered up past Papal censors.

But that very sense of turbulence may be what makes this work resonate today. Its boisterous bodies arrested in tortured move are precisely what makes information technology unequivocally Michelangelo, even equally his afterward piece of work leaves behind the divine harmony of the High Renaissance for something more mannerist—and modernistic.

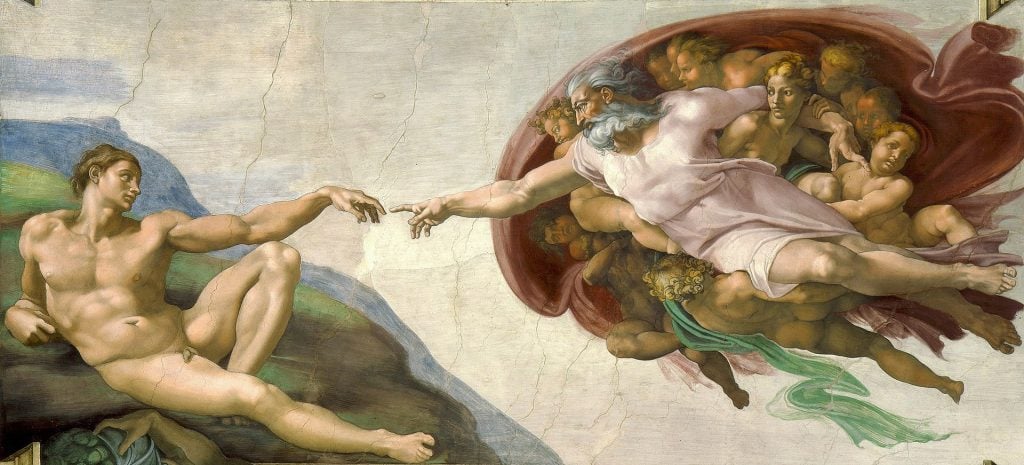

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Cosmos of Adam in the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican Museums, Rome.

ii. The Creation of Adam (1508-12)

Pope Julius 2 paused Michelangelo'south long labor on the papal tomb to pigment the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The creative person wasn't interested in accepting the commission—he was a sculptor, non a painter, after all—but he was pressured into it. Then information technology was that Michelangelo, the supreme sculptor, created what is probably one of the most sacred images of Western art history.

At the center of the ballsy work is the Creation: God extends his finger toward the hand a newly minted man, Adam, about to imbue him with life (Eve watches from the crook of God's arm). Few artists had always depicted the scene every bit dramatically every bit Michelangelo, and fifty-fifty in our secular age, it has fabricated it virtually metonymic for the unabridged story of Genesis in contemporary culture. Information technology is so oft invoked, cited, or riffed on for its religious meaning that it may actually be possible to forget just what a terrific act of artistic theater it is.

That's what Paul Barolsky suggests in his impassioned essay "The Genius of Michelangelo's Cosmos of Adam and the Blindness of Fine art History":

What makes Michelangelo's fresco and so absorbing is its tension—the sense of an effect that will just be consummate when the finger of God touches that of Adam. God, in Michelangelo'south fresco, is suspended forever, we might say, in the incomplete human action of filling Adam with the spirit. This is the ultimate divine non finito… In our post-Christian world, mod scholars are not securely concerned with he spatial pregnant of the fresco, and that is understandable. Only to ignore the style in which Michelangelo made his meaning visible is to be blind to a striking manifestation of artistic genius or poetic imagination.

If it were some other artist, this incredibly creative delineation of Creation would top whatever list. Except this is not any other artist, which brings me to…

Michelangelo, David (1501–04). Collection of the Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence.

one. David (1501-04)

It has to be David, correct?

The artist was merely 26 when he sculpted David. Even at the time information technology brought him to the heights of artistic fame for its sheer bravura. Standing at more than 13 anxiety tall, the work was sculpted from a slice of marble that some other creative person had started carving into for some other project only then abandoned considering the stone was structurally compromised. This didn't deter Michelangelo, though, who knew he had the skills to make the marble work for him.

"To be certain, anyone who sees this statue demand non be concerned with seeing any other piece of sculpture done in our times or in whatever other period by any other creative person," Vasari wrote in the Lives of the Artists, making Michelangelo the key character in his ur-art history volume, the nearly vaunted figure of the Renaissance.

TheDavid is different than whatever sculpture that came before. It is drawn from the well-known Biblical story of a young boy fighting the behemothic Goliath. Merely while others chose to emphasize his smallness, Michelangelo'south David is a giant himself: A muscular, confident homo prepared for boxing. The amazing thing, then and now, about Michelangelo'southward David is that the work is both literally a depiction of a larger-than-life hero, and the quintessential depiction of the plucky little guy.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay alee of the art earth? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive disquisitional takes that drive the chat forward.

Source: https://news.artnet.com/opinion/michelangelos-10-most-popular-works-ranked-1144943

0 Response to "Which Artists Second Most Famous Work of Art Was Created Not Standing Up or Sitting Down?"

Post a Comment